A Friend Indeed 181012

/Sherman Fairchild

Paul Klipsch has been considered by many to be the epitome of the “self-made man”. However, he would be quick to tell you that he “stood on the shoulders of giants”. Having friends in strategic places also greased the skids for Paul. While we do not have his earliest contacts with Sherman Fairchild, it is clear from over 200 pages of correspondence that this industry titan took many opportunities to help out “the little guy”. Never heard of Fairchild? Take a look at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sherman_Fairchild.

The earliest correspondence so far discovered is from May 1944. Paul wrote to Sherman about the lack of bass response from Sherman’s 1943 “Klipschorn” woofer. The woofer was built by Sherman’s carpenter from early drawings supplied by PWK, and it still utilized a 12” driver. The system was illustrated in The Architectural Forum of April 1943. This was before Paul’s own HF horn was designed, so a Western Electric multicell horn was utilized. Paul’s bass performance “diagnosis by letter” took quite a while, but eventually resulted in his visit to Sherman’s New York City penthouse, and the application of “about 2 pounds of putty” to stop some serious air-leaks. Earlier correspondence to Sherman from Altec Lansing’s John Hilliard https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Kenneth_Hilliard expressed Hilliard’s doubt in the performance of the yet-to-be named Klipschorn, as compared to larger cinema speakers. The putty removed those doubts!

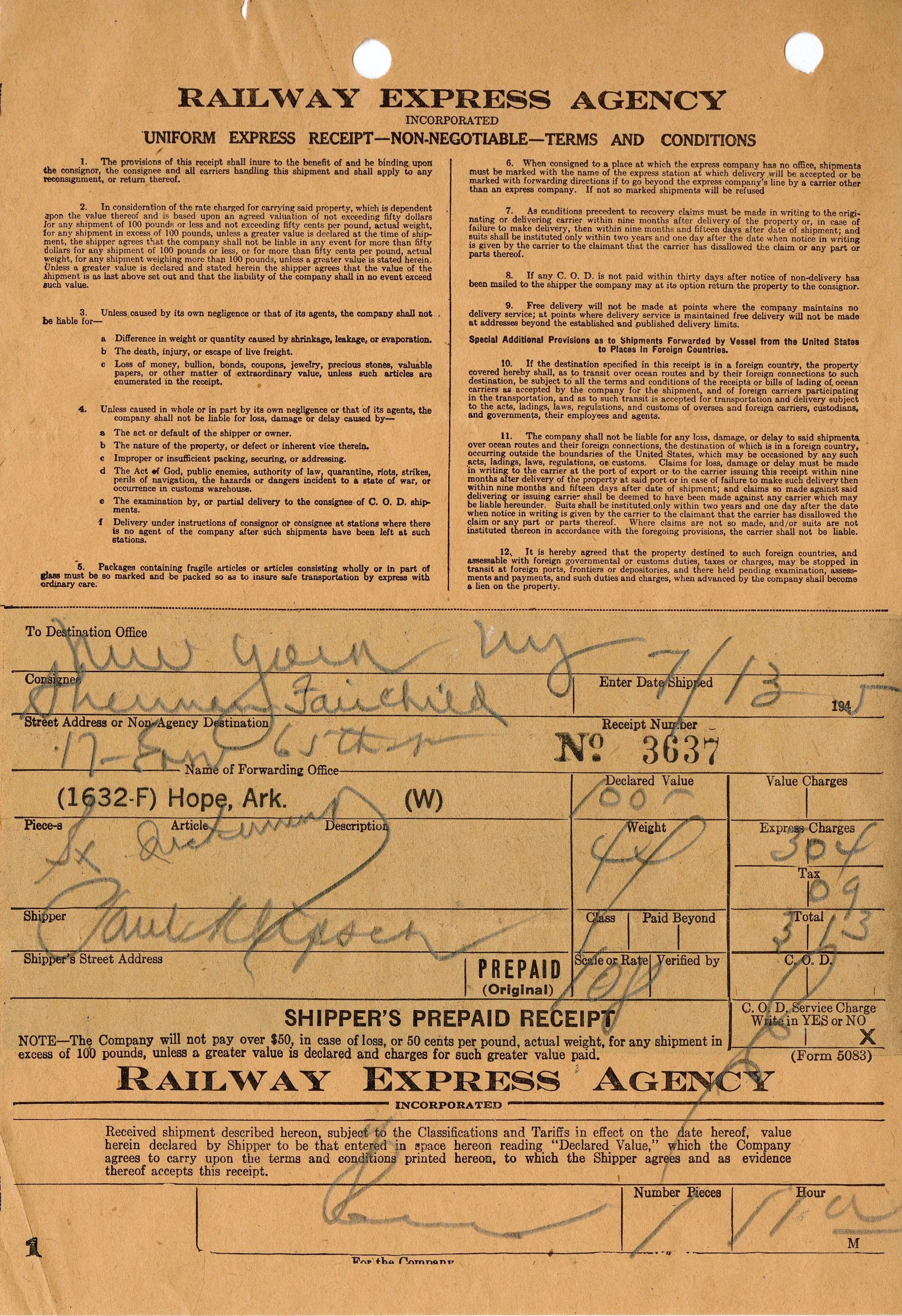

Late in 1944 Paul related to Sherman that he was working on his own HF horn design. In his words: “I need about a 4 x 4 foot sheet of ½ inch plywood……. This is funny but I can’t laugh; the proving ground yard is well-stocked with ½ inch stuff but I can’t buy it and I won’t steal it!” Guess who sent him a sheet from New York City? Paul was able to build two K-5 prototype horns: the one we currently have on display in the Museum, and one that was sent to Sherman on July 13, 1945.

Sherman was eight years Paul’s senior. A letter from Paul in June contained the sentence: “If you have any “fatherly advice” or suggestions I would like to hear them.” On July 9th Sherman writes:

“I am trying to get you the articles which you mention in your letter of June 30th.

You have my permission to say anything you like about me or the speaker in the article you are preparing. It will not be necessary for me to see it before it is published but if it is convenient for you to send me a proof, I would appreciate it.”

Clearly Sherman is engaging the power of his industrial empire to find technical articles for Paul, and he appears to have complete trust in Paul’s use of his name.

By October of 1945 Paul’s intention to “change careers” elicited Sherman’s advice on possible manufacturing scenarios, and even his offer of “making a small financial contribution.” In November he offered Paul his contacts in the molding industry for realization of a manufacturing method for the K-5 horn. The next year Sherman supplied a recommendation for a representative in the Los Angeles area. The list goes on, but it should be obvious that developing a relationship with Mr. Fairchild materially aided in the debut of the Klipschorn.

Among the many non-speaker topics contained in their correspondence was a discussion of post-war airplanes. Paul revealed in a December 1944 letter: “I have a few hours stick time in ships ranging from the Piper Cub to the B25.” He went on to provide Sherman his “requirements” for a personal airplane. Sherman’s response suggested that most military airplanes run about $5.00 per pound. The maker of the P-47 (another manufacturer) predicted that it would be possible to produce an all-metal, post-war plane for around $1.00 per pound. Sherman concluded his letter with a “wait and see” caution.

Copyright 2018 Jim Hunter and KHMA, Inc.